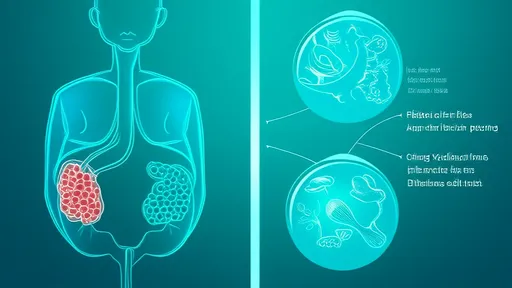

In the evolving landscape of nutritional science, resistant starch has emerged as a fascinating subject, capturing the attention of researchers, health professionals, and food enthusiasts alike. Unlike typical dietary starch, which is broken down and absorbed in the small intestine, resistant starch, as its name implies, resists digestion, traveling to the large intestine where it serves as a prebiotic, feeding the beneficial gut microbiota. This unique property underpins its significant health implications, ranging from improved glycemic control to enhanced digestive health. To fully appreciate its benefits, it is crucial to understand its classification into four distinct types: RS1, RS2, RS3, and RS4, each with unique functional characteristics and sources within our food supply.

RS1, or physically inaccessible starch, is found in grains, seeds, and legumes where the starch is trapped within a fibrous matrix, making it physically resistant to the action of digestive enzymes. Think of a whole grain or a bean; its cellular structure acts as a natural barrier. The functionality of RS1 is highly dependent on food processing; milling or grinding these foods can break down the cell walls, rendering the starch accessible and digestible, thereby reducing its resistant fraction. Therefore, to harness the benefits of RS1, consuming whole or minimally processed forms of these foods is key. Dietary sources rich in RS1 include whole grains like wheat and barley, legumes such as lentils and chickpeas, and seeds. Its primary functional role in the diet is to contribute to a slower, more controlled release of energy and to increase dietary fiber intake, which promotes satiety and supports a healthy digestive system by reaching the colon intact.

RS2, or resistant starch granules, represents starch that is indigestible in its raw, native state due to its granule structure. This type of starch is naturally found in uncooked foods like raw potatoes, green (unripe) bananas, and some high-amylose corn varieties. The granule's semi-crystalline structure is simply too compact for our digestive enzymes to penetrate effectively. However, this resistance is often temporary. The application of heat through cooking gelatinizes the starch, disrupting its structure and making it largely digestible. This is why a cooked potato is a source of readily available carbohydrate, while a raw potato is not. The functional benefit of RS2 is most potent when these foods are consumed raw or, in the case of high-amylose corn, specially processed to retain its resistant properties. It serves as an excellent prebiotic, fostering the growth of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus in the gut.

The third category, RS3 or retrograded starch, is not present in foods naturally but is formed through a process called retrogradation. When starchy foods like potatoes, rice, or pasta are cooked and then allowed to cool, some of the digestible starch recrystallizes into a form that enzymes can no longer break down easily. This is a fascinating example of how food preparation can fundamentally alter its nutritional profile. The formation of RS3 is influenced by several factors, including the amylose content of the food (higher amylose promotes more retrogradation), the cooking temperature, and the cooling time. Foods that are excellent sources of RS3 include cooled potatoes (potato salad), sushi rice, and stale bread. Functionally, RS3 is particularly valued for its stability; it remains resistant even upon reheating, making it a practical way to incorporate resistant starch into a warmed meal. Its resilience allows it to reliably reach the colon, where it contributes significantly to the production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids like butyrate.

RS4, or chemically modified starch, stands apart from the others as it is a product of human ingenuity rather than nature. Through various chemical processes, the structure of starch molecules is altered to create bonds that are completely indigestible by human enzymes. This modification is not a random occurrence but a controlled industrial process designed to impart specific functional properties to food, such as improved texture, stability, and shelf life, while also adding nutritional value in the form of dietary fiber. You will find RS4 in a variety of commercially prepared foods, often listed on labels as "modified food starch," and it is also available as a standalone fiber supplement. Its primary functional characteristic is its complete resistance to digestion, regardless of processing methods like heating, cooling, or pH changes. This makes it an incredibly versatile tool for food manufacturers to boost the fiber content of products like bread, cereals, and pasta without altering their taste or texture significantly.

Understanding the distinct functionalities of these four types reveals a broader narrative about diet and health. RS1 teaches us the value of consuming whole foods in their natural, unrefined state. RS2 highlights the impact of food preparation, showing that sometimes less processing is more. RS3 demonstrates the dynamic nature of food, where a simple act like cooling can transform a digestible carbohydrate into a beneficial prebiotic. Finally, RS4 showcases how food technology can be leveraged to create functional ingredients that address modern dietary needs. Together, they offer a multifaceted approach to increasing resistant starch intake. Incorporating a variety of these sources—from a bowl of lentil soup and a green banana smoothie to a serving of potato salad and fiber-enriched whole-grain bread—can synergistically support gut health, improve metabolic parameters, and contribute to overall well-being in a significant and scientifically substantiated way.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025