The desert ant Cataglyphis is a master navigator of barren landscapes, a tiny creature that forages under the blazing sun with a precision that belies its minuscule brain. It ventures hundreds of meters from its nest in search of food, a journey across a featureless terrain of sand and rock where landmarks are scarce and the heat is lethal. Yet, it consistently finds its way back along a near-straight line to its nest entrance, a hole barely visible in the vastness. This remarkable feat, known as path integration, relies on an internal pedometer to count steps and, most crucially, a celestial compass that reads the pattern of polarized light in the sky. The neural machinery behind this polarized light navigation is a breathtaking example of evolutionary miniaturization and efficiency, a biological marvel that has captivated scientists for decades.

Skylight polarization is a phenomenon caused by the scattering of sunlight in the atmosphere. This creates a pattern of polarized light—light waves oscillating in a specific plane—that forms a band across the sky, the exact pattern of which changes predictably with the sun's position. While invisible to humans without filters, many insects, including the desert ant, perceive this pattern through specialized structures in their compound eyes. For the ant, this pattern is not a vague glow but a dynamic compass dial painted across the dome of the sky, providing a constant directional reference as long as the sun, or even a small patch of blue sky, is visible.

The first stage of this sophisticated navigation system is the physical capture of this polarized light signal. This task falls to a specific region in the dorsal-most part of the ant's compound eye, an area named the dorsal rim area (DRA). The ommatidia, or individual eye units, in the DRA are uniquely adapted for this purpose. Their photoreceptor cells are highly sensitive to the angle of polarized light. Crucially, the microvilli—the light-sensitive structures within these cells—are aligned in two predominant, orthogonal directions. This arrangement allows the ant to perform a form of neural comparison, effectively measuring the e-vector (the direction of oscillation) of the incoming polarized light. This raw data is the fundamental input for the ant's celestial compass.

This raw visual information is then relayed from the retina to the first neuropil of the insect brain, the lamina, and then proceeds to the second neuropil, the medulla. It is here, within a small and specialized region of the medulla, that the initial processing of polarization data begins. Neurons in this region start the complex task of integrating signals from multiple DRA photoreceptors with differing microvillar alignments. This integration is essential for creating a more robust and noise-resistant signal, filtering out irrelevant visual clutter to isolate the crucial directional information encoded in the sky's polarization pattern.

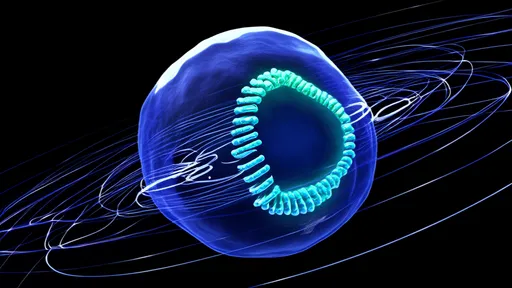

The processed information then makes a pivotal journey into the central complex, a intricate set of neuropils in the center of the insect brain that acts as the central processing unit for spatial orientation and navigation. Within the central complex, specifically in the ellipsoid body, lies the heart of the compass. Research has revealed a stunning neural architecture here: a ring of neurons whose activity forms a bump of neural excitation. As the ant rotates its body, this activity bump rotates around the ring of neurons, faithfully tracking the animal's heading in relation to the polarized light cue from the sky. This internal representation is a true neural compass, a continuous readout of the ant's current direction in its world.

The genius of this system lies in its translation of an abstract visual pattern into a concrete directional signal. The brain does not simply see "polarization"; it interprets it as a heading. The neural circuitry within the central complex is thought to compare the incoming, constantly updating polarization signal from the eyes against an internal template or model of the expected polarization pattern for a given solar position. Through this continuous comparison, the animal can determine its heading relative to a desired direction, such as the direction back to the nest. This allows it to make course corrections on the fly, maintaining a straight path home.

Path integration is the computational culmination of this process. The ant's brain is continuously performing a complex mathematical operation, integrating its heading (provided by the polarized light compass) with its velocity and distance traveled (likely provided by step-counting and optic flow) to constantly update its vector to the nest. This is a real-time, dead-reckoning system. The neural compass in the central complex provides the directional component of this vector, and it is believed that the adjacent protocerebral bridge structure may encode the distance component. Together, they form a unified neural representation of the homing vector, guiding the ant with astonishing accuracy.

The evolutionary pressures of the desert environment have sculpted this system to be exceptionally robust. The ant's compass can function with only a small patch of clear sky, an vital adaptation for an animal that may encounter obstacles or need to navigate under partially cloudy conditions. Furthermore, the system demonstrates a degree of plasticity and learning. While the basic template for decoding polarized light is innate, ants can recalibrate their compass systems based on new visual experiences, ensuring its accuracy throughout their lives. This combination of hardwired precision and adaptive learning makes the system both reliable and flexible.

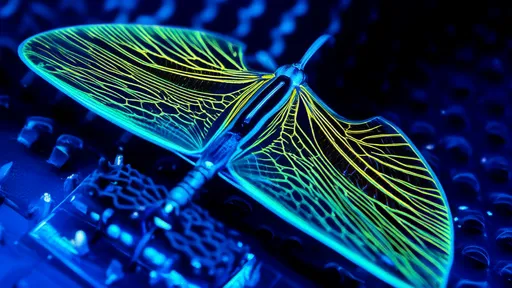

Studying the desert ant's neural mechanisms offers far more than just a fascinating glimpse into the insect world. It provides a powerful model for understanding fundamental principles of sensory processing, neural computation, and navigation. Bioengineers and roboticists are deeply interested in reverse-engineering this compact and energy-efficient system. The creation of artificial polarized light sensors and algorithms inspired by the ant's brain could lead to major advancements in autonomous robot navigation, particularly for vehicles or drones that must operate in GPS-denied environments, such as on other planets, underwater, or in complex urban canyons. The humble desert ant, therefore, is guiding not only itself home but also pointing the way toward new frontiers in technology.

In conclusion, the journey of the desert ant from foraging site to nest is a silent epic written in neural impulses and interpreted through the lens of polarized light. From the specialized photoreceptors of the dorsal rim area to the sophisticated ring attractor network in the central complex, every stage of this process is a marvel of biological engineering. It is a powerful testament to the fact that profound computational complexity can be achieved within a tiny brain, offering elegant solutions to the universal challenge of navigation. The ant does not ponder the sky's mysteries, but its brain deciphers them with an efficiency that continues to inspire awe and scientific discovery.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025