In the intricate dance of aerial mastery, few creatures command the skies with the precision and grace of the dragonfly. For centuries, observers have marveled at its acrobatic prowess—its ability to hover, dart, reverse, and accelerate with seemingly effortless control. While human aviation has relied on rigid, fixed-wing designs and powerful engines to achieve flight, the dragonfly operates on an entirely different principle, one honed by over 300 million years of evolutionary refinement. The secret to its unparalleled aerodynamic performance lies not in brute force, but in the elegant, complex architecture of its wings, specifically the intricate network of veins that form its structure. This is not merely a frame; it is a dynamic, fluid-responsive system that continues to baffle and inspire aerospace engineers seeking the next frontier in efficient flight.

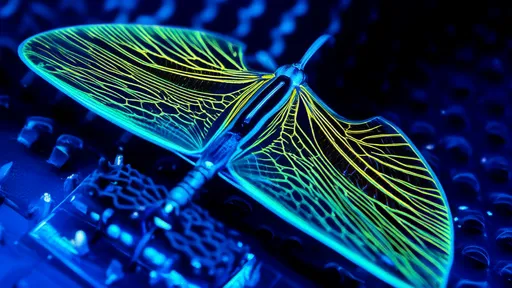

The dragonfly wing is a masterpiece of biological engineering. Unlike the stiff, solid wings of an airplane or the membranous sails of other insects, it is a complex composite material. A delicate membrane is stretched over a sophisticated lattice of veins, forming a corrugated pattern of peaks and valleys. This is the first clue to its performance. For decades, conventional aerodynamics would have suggested that such a rough, uneven surface would create excessive drag, making it highly inefficient. However, nature operates on a different set of rules, rules we are only beginning to understand through advanced computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and high-speed imaging.

The key to unlocking the dragonfly's secret is in the interaction between this corrugated structure and the air flowing over it. At the scale and speeds at which a dragonfly operates, air behaves less like a smooth, continuous fluid and more like a viscous medium. Here, the Reynolds number—a dimensionless quantity that predicts flow patterns—is relatively low. In this regime, the corrugations on the wing play a critical role. Research has revealed that these ridges do not hinder airflow; instead, they stabilize vortices, small regions of swirling air, along the valleys. These trapped vortices act as a buffer, effectively smoothing the passage of air over the wing and reducing overall drag. It’s a paradoxical phenomenon: a rough surface creating a smoother aerodynamic profile than a perfectly smooth one could under the same conditions.

Beyond passive drag reduction, the venation network is a dynamic shock absorber. During the rapid and complex flapping motion that characterizes insect flight, the wings are subjected to enormous and rapidly changing forces. A perfectly rigid wing would be prone to catastrophic failure under such stress. The dragonfly’s wing, however, exhibits controlled flexibility. The pattern of veins—with thicker, stronger veins like the costa and subcosta forming a leading-edge spar, and finer, more flexible veins filling the rest of the panel—allows the wing to twist and deform elastically with each stroke.

This controlled deformation is not a flaw; it is a feature. It allows the wing to automatically adjust its angle of attack throughout the stroke cycle, optimizing lift generation. Furthermore, this flexibility mitigates the effects of gusty or turbulent wind conditions, allowing the dragonfly to maintain stability where a rigid-winged micro-drone would be thrown off course. The veins essentially form a smart, responsive grid that distributes and manages aerodynamic and inertial loads intelligently, preventing material fatigue and enabling the incredible maneuverability we observe.

The most profound aerodynamic advantage, however, may lie in the wing's ability to manipulate leading-edge vortices (LEVs). In flapping flight, a high-angle attack can cause the airflow to separate from the top of the wing, forming a powerful vortex that, if sustained, can dramatically enhance lift. This is a well-known phenomenon in rotary-wing aerodynamics. The challenge has always been controlling this vortex. In most cases, it detaches and is shed, causing instability and a loss of lift.

Studies using particle image velocimetry to visualize airflow around robotic dragonfly wings have shown something remarkable. The combination of the corrugated structure and the wing's flexing motion appears to anchor the leading-edge vortex throughout the entire downstroke. The corrugations help to pin the vortex core in place, preventing its premature shedding and ensuring a consistent region of low pressure over the wing. This stable, attached vortex generates a tremendous amount of extra lift, providing the powerful thrust needed for the dragonfly’s explosive take-offs and sustained hovering. It’s like having a permanent, built-in lift-enhancing device that requires no moving parts.

Inspired by these principles, the field of biomimetics is actively seeking to translate the dragonfly’s secrets into human technology. Aerospace engineers are now designing micro-air vehicles (MAVs) with wings that mimic the corrugated venation patterns. These bio-inspired drones promise significantly greater efficiency, longer flight times, and enhanced resilience in unpredictable aerial environments. The potential applications are vast, ranging from search-and-rescue missions in collapsed buildings to advanced agricultural monitoring and even exploration of other planets with atmospheres, like Mars.

The implications extend beyond tiny drones. The principles of vortex stabilization and passive flow control learned from dragonfly wings could inform the design of next-generation aircraft winglets, turbine blades, and propellers. By incorporating strategically placed ridges or flexible elements, engineers could reduce drag, increase lift, and decrease the noise signature of larger aircraft, leading to more fuel-efficient and environmentally friendly aviation.

The humble dragonfly, often seen as a simple summer insect, is in reality a bearer of profound aerodynamic wisdom. Its wings are not just tools for flight; they are highly evolved instruments fine-tuned by natural selection to master the fluid dynamics of air. The optimization of its venation network for vortex control, load distribution, and adaptive flexibility represents a pinnacle of evolutionary engineering. As we continue to decode these ancient secrets, we are not just learning about the natural world; we are unlocking new possibilities for our own technological future, one inspired by the silent, efficient flight of a creature that has soared through the ages.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025